Elizabeth I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and

Elizabeth was born at

Elizabeth was born at  Elizabeth's first

Elizabeth's first

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife

For several years she also seriously negotiated to marry Philip's cousin

For several years she also seriously negotiated to marry Philip's cousin

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body.

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body.

Elizabeth's first policy toward

Elizabeth's first policy toward

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne.Loades, 73. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful,

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a major Catholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry her to Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the English throne.Loades, 73. After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them were executed on Elizabeth's orders. In the belief that the revolt had been successful,

After the occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562–1563, Elizabeth avoided military expeditions on the continent until 1585, when she sent an English army to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip II.Haigh, 135. This followed the deaths in 1584 of the queen's allies

After the occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562–1563, Elizabeth avoided military expeditions on the continent until 1585, when she sent an English army to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels against Philip II.Haigh, 135. This followed the deaths in 1584 of the queen's allies

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced. Elizabeth's procession to a thanksgiving service at

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced. Elizabeth's procession to a thanksgiving service at

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited the French throne in 1589, Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her first venture into France since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's succession was strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, and Elizabeth feared a Spanish takeover of the channel ports.

The subsequent English campaigns in France, however, were disorganised and ineffective.Haigh, 142. Peregrine Bertie, largely ignoring Elizabeth's orders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an army of 4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1589, having lost half his troops. In 1591, the campaign of John Norreys, who led 3,000 men to

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited the French throne in 1589, Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her first venture into France since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's succession was strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, and Elizabeth feared a Spanish takeover of the channel ports.

The subsequent English campaigns in France, however, were disorganised and ineffective.Haigh, 142. Peregrine Bertie, largely ignoring Elizabeth's orders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an army of 4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1589, having lost half his troops. In 1591, the campaign of John Norreys, who led 3,000 men to

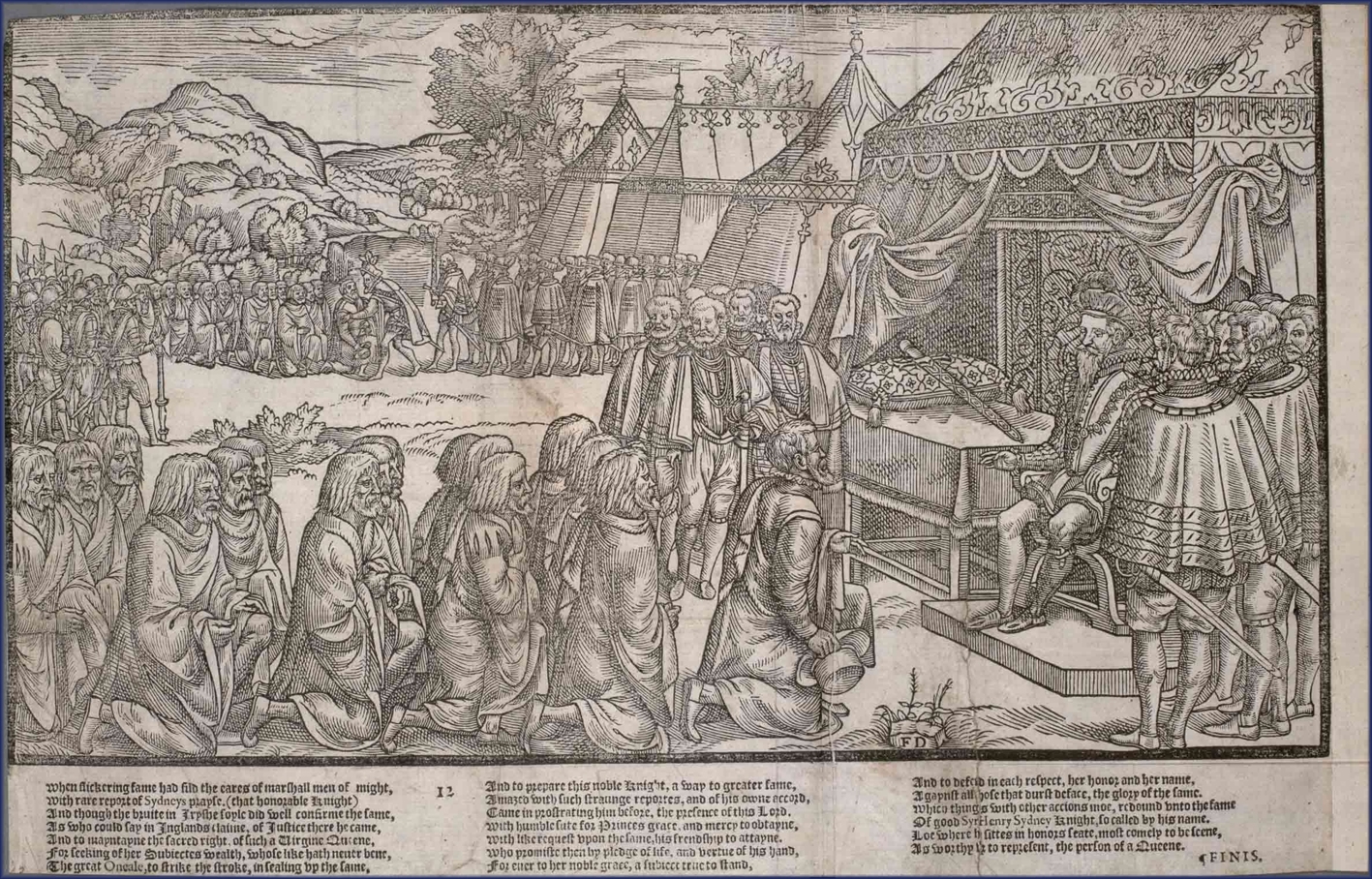

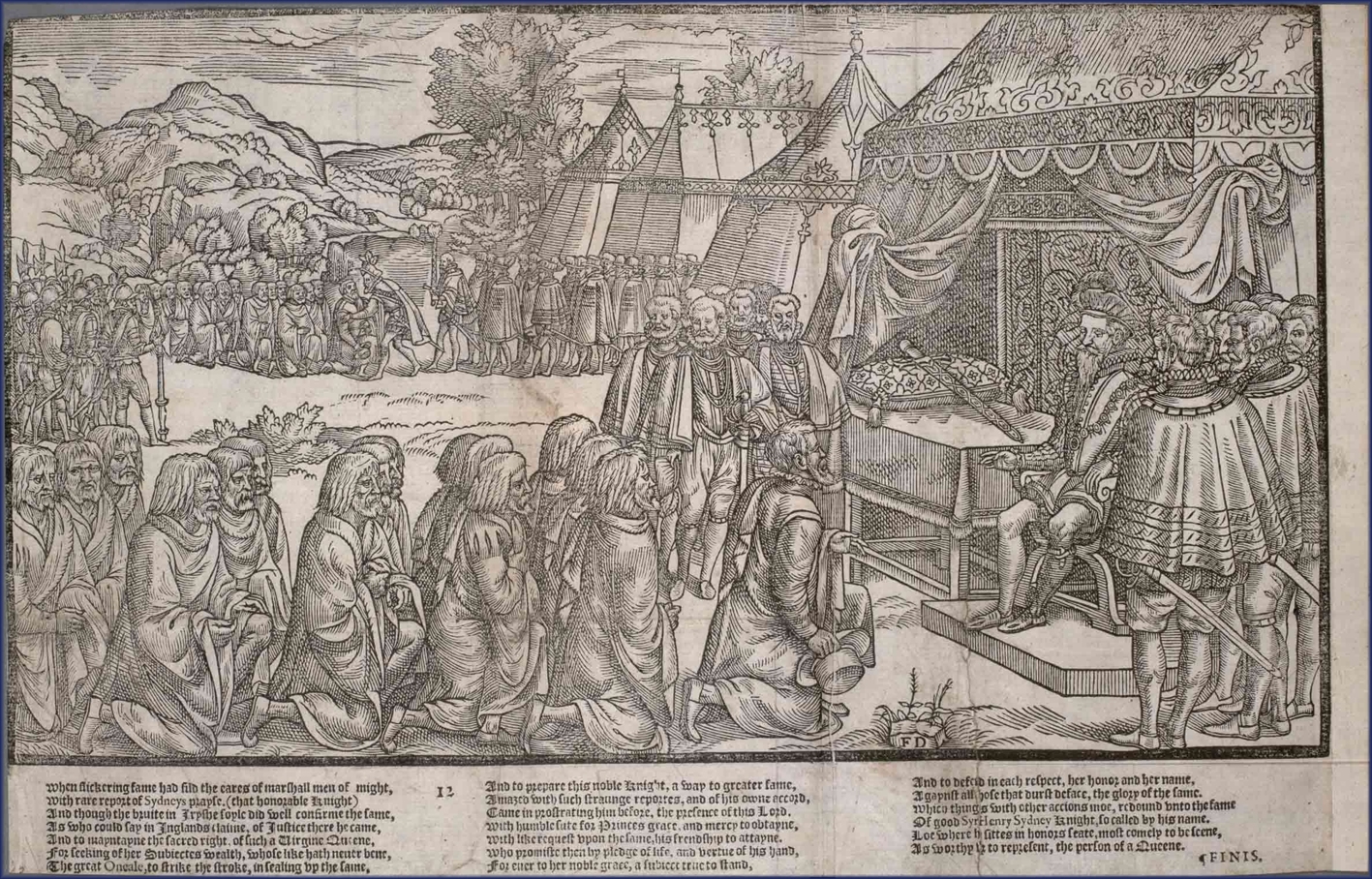

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms, Elizabeth faced a hostile, and in places virtually autonomous, Irish population that adhered to Catholicism and was willing to defy her authority and plot with her enemies. Her policy there was to grant land to her courtiers and prevent the rebels from giving Spain a base from which to attack England. In the course of a series of uprisings, Crown forces pursued

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms, Elizabeth faced a hostile, and in places virtually autonomous, Irish population that adhered to Catholicism and was willing to defy her authority and plot with her enemies. Her policy there was to grant land to her courtiers and prevent the rebels from giving Spain a base from which to attack England. In the course of a series of uprisings, Crown forces pursued

Trade and diplomatic relations developed between England and the Barbary states during the rule of Elizabeth. England established a trading relationship with

Trade and diplomatic relations developed between England and the Barbary states during the rule of Elizabeth. England established a trading relationship with

Tate.org.uk

Elizabeth "agreed to sell munitions supplies to Morocco, and she and Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur talked on and off about mounting a joint operation against the Spanish".Kupperman, 39. Discussions, however, remained inconclusive, and both rulers died within two years of the embassy. Diplomatic relations were also established with the

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called, was the changed character of Elizabeth's governing body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generation was in power. With the exception of William Cecil, Baron Burghley, the most important politicians had died around 1590: the Earl of Leicester in 1588; Francis Walsingham in 1590; and Christopher Hatton in 1591. Factional strife in the government, which had not existed in a noteworthy form before the 1590s, now became its hallmark. A bitter rivalry arose between Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, with both being supported by their respective adherents. The struggle for the most powerful positions in the state marred the kingdom's politics. The queen's personal authority was lessening, as is shown in the 1594 affair of Dr. Roderigo Lopes, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she could not prevent the doctor's execution, although she had been angry about his arrest and seems not to have believed in his guilt.

During the last years of her reign, Elizabeth came to rely on the granting of monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage, rather than asking Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war. The practice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment. This culminated in agitation in the House of Commons during the parliament of 1601. In her famous "Golden Speech" of 30 November 1601 at Whitehall Palace to a deputation of 140 members, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses, and won the members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions:

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it is sometimes called, was the changed character of Elizabeth's governing body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generation was in power. With the exception of William Cecil, Baron Burghley, the most important politicians had died around 1590: the Earl of Leicester in 1588; Francis Walsingham in 1590; and Christopher Hatton in 1591. Factional strife in the government, which had not existed in a noteworthy form before the 1590s, now became its hallmark. A bitter rivalry arose between Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, Robert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, with both being supported by their respective adherents. The struggle for the most powerful positions in the state marred the kingdom's politics. The queen's personal authority was lessening, as is shown in the 1594 affair of Dr. Roderigo Lopes, her trusted physician. When he was wrongly accused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, she could not prevent the doctor's execution, although she had been angry about his arrest and seems not to have believed in his guilt.

During the last years of her reign, Elizabeth came to rely on the granting of monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage, rather than asking Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war. The practice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers at the public's expense, and widespread resentment. This culminated in agitation in the House of Commons during the parliament of 1601. In her famous "Golden Speech" of 30 November 1601 at Whitehall Palace to a deputation of 140 members, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses, and won the members over with promises and her usual appeal to the emotions:

This same period of economic and political uncertainty, however, produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England. The first signs of a new literary movement had appeared at the end of the second decade of Elizabeth's reign, with John Lyly's ''Euphues'' and

This same period of economic and political uncertainty, however, produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England. The first signs of a new literary movement had appeared at the end of the second decade of Elizabeth's reign, with John Lyly's ''Euphues'' and

Elizabeth's senior adviser, Lord Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. His political mantle passed to his son Robert, who soon became the leader of the government. One task he addressed was to prepare the way for a succession to Elizabeth I of England, smooth succession. Since Elizabeth would never name her successor, Robert Cecil was obliged to proceed in secret. He therefore entered into a Secret correspondence of James VI, coded negotiation with

Elizabeth's senior adviser, Lord Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. His political mantle passed to his son Robert, who soon became the leader of the government. One task he addressed was to prepare the way for a succession to Elizabeth I of England, smooth succession. Since Elizabeth would never name her successor, Robert Cecil was obliged to proceed in secret. He therefore entered into a Secret correspondence of James VI, coded negotiation with  The queen's health remained fair until the autumn of 1602, when a series of deaths among her friends plunged her into a severe depression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friend Catherine Carey, Lady Knollys, came as a particular blow. In March, Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled and unremovable melancholy", and sat motionless on a cushion for hours on end. When Robert Cecil told her that she must go to bed, she snapped: "Must is not a word to use to princes, little man." She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace, between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil and the council set their plans in motion and proclaimed James King of England.

While it has become normative to record Elizabeth's death as occurring in 1603, following Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, English calendar reform in the 1750s, at the time England observed New Year's Day on 25 March, commonly known as Lady Day. Thus Elizabeth died on the last day of the year 1602 in the old calendar. The modern convention is to use the old style calendar for the day and month while using the new style calendar for the year.

The queen's health remained fair until the autumn of 1602, when a series of deaths among her friends plunged her into a severe depression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friend Catherine Carey, Lady Knollys, came as a particular blow. In March, Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled and unremovable melancholy", and sat motionless on a cushion for hours on end. When Robert Cecil told her that she must go to bed, she snapped: "Must is not a word to use to princes, little man." She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace, between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil and the council set their plans in motion and proclaimed James King of England.

While it has become normative to record Elizabeth's death as occurring in 1603, following Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, English calendar reform in the 1750s, at the time England observed New Year's Day on 25 March, commonly known as Lady Day. Thus Elizabeth died on the last day of the year 1602 in the old calendar. The modern convention is to use the old style calendar for the day and month while using the new style calendar for the year.

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at night to Palace of Whitehall, Whitehall, on a barge lit with torches. At her funeral on 28 April, the coffin was taken to

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at night to Palace of Whitehall, Whitehall, on a barge lit with torches. At her funeral on 28 April, the coffin was taken to

Elizabeth was lamented by many of her subjects, but others were relieved at her death.Loades, 100–101. Expectations of King James started high but then declined. By the 1620s, there was a nostalgic revival of the cult of Elizabeth.Somerset, 726. Elizabeth was praised as a heroine of the Protestant cause and the ruler of a golden age. James was depicted as a Catholic sympathiser, presiding over a corrupt court. The triumphalist image that Elizabeth had cultivated towards the end of her reign, against a background of factionalism and military and economic difficulties, was taken at face value and her reputation inflated. Godfrey Goodman, Bishop of Gloucester, recalled: "When we had experience of a Scottish government, the Queen did seem to revive. Then was her memory much magnified." Elizabeth's reign became idealised as a time when crown, church and parliament had worked in constitutional balance.

The picture of Elizabeth painted by her Protestant admirers of the early 17th century has proved lasting and influential. Her memory was also revived during the Napoleonic Wars, when the nation again found itself on the brink of invasion.Dobson and Watson, 258. In the Victorian era, the Elizabethan legend was adapted to the imperial ideology of the day, and in the mid-20th century, Elizabeth was a romantic symbol of the national resistance to foreign threat. Historians of that period, such as J. E. Neale (1934) and A. L. Rowse (1950), interpreted Elizabeth's reign as a golden age of progress. Neale and Rowse also idealised the Queen personally: she always did everything right; her more unpleasant traits were ignored or explained as signs of stress.

Recent historians, however, have taken a more complicated view of Elizabeth. Her reign is famous for the defeat of the Armada, and for successful raids against the Spanish, such as those on Cádiz in 1587 and 1596, but some historians point to military failures on land and at sea. In Ireland, Elizabeth's forces ultimately prevailed, but their tactics stain her record. Rather than as a brave defender of the Protestant nations against Spain and the Habsburgs, she is more often regarded as cautious in her foreign policies. She offered very limited aid to foreign Protestants and failed to provide her commanders with the funds to make a difference abroad.

Elizabeth established an English church that helped shape a national identity and remains in place today. Those who praised her later as a Protestant heroine overlooked her refusal to drop all practices of Catholic origin from the Church of England. Historians note that in her day, strict Protestants regarded the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, Acts of Settlement and Uniformity of 1559 as a compromise. In fact, Elizabeth believed that faith was personal and did not wish, as Francis Bacon put it, to "make windows into men's hearts and secret thoughts".

Though Elizabeth followed a largely defensive foreign policy, her reign raised England's status abroad. "She is only a woman, only mistress of half an island," marvelled Pope Sixtus V, "and yet she makes herself feared by Spain, by France, by Holy Roman Empire, the Empire, by all".Somerset, 727. Under Elizabeth, the nation gained a new self-confidence and sense of sovereignty, as Christendom fragmented. Elizabeth was the first Tudor to recognise that a monarch ruled by popular consent. She therefore always worked with parliament and advisers she could trust to tell her the truth—a style of government that her Stuart successors failed to follow. Some historians have called her lucky; she believed that God was protecting her. Priding herself on being "mere English", Elizabeth trusted in God, honest advice, and the love of her subjects for the success of her rule.Starkey ''Elizabeth: Woman'', 6–7. In a prayer, she offered thanks to God that:

Elizabeth was lamented by many of her subjects, but others were relieved at her death.Loades, 100–101. Expectations of King James started high but then declined. By the 1620s, there was a nostalgic revival of the cult of Elizabeth.Somerset, 726. Elizabeth was praised as a heroine of the Protestant cause and the ruler of a golden age. James was depicted as a Catholic sympathiser, presiding over a corrupt court. The triumphalist image that Elizabeth had cultivated towards the end of her reign, against a background of factionalism and military and economic difficulties, was taken at face value and her reputation inflated. Godfrey Goodman, Bishop of Gloucester, recalled: "When we had experience of a Scottish government, the Queen did seem to revive. Then was her memory much magnified." Elizabeth's reign became idealised as a time when crown, church and parliament had worked in constitutional balance.

The picture of Elizabeth painted by her Protestant admirers of the early 17th century has proved lasting and influential. Her memory was also revived during the Napoleonic Wars, when the nation again found itself on the brink of invasion.Dobson and Watson, 258. In the Victorian era, the Elizabethan legend was adapted to the imperial ideology of the day, and in the mid-20th century, Elizabeth was a romantic symbol of the national resistance to foreign threat. Historians of that period, such as J. E. Neale (1934) and A. L. Rowse (1950), interpreted Elizabeth's reign as a golden age of progress. Neale and Rowse also idealised the Queen personally: she always did everything right; her more unpleasant traits were ignored or explained as signs of stress.

Recent historians, however, have taken a more complicated view of Elizabeth. Her reign is famous for the defeat of the Armada, and for successful raids against the Spanish, such as those on Cádiz in 1587 and 1596, but some historians point to military failures on land and at sea. In Ireland, Elizabeth's forces ultimately prevailed, but their tactics stain her record. Rather than as a brave defender of the Protestant nations against Spain and the Habsburgs, she is more often regarded as cautious in her foreign policies. She offered very limited aid to foreign Protestants and failed to provide her commanders with the funds to make a difference abroad.

Elizabeth established an English church that helped shape a national identity and remains in place today. Those who praised her later as a Protestant heroine overlooked her refusal to drop all practices of Catholic origin from the Church of England. Historians note that in her day, strict Protestants regarded the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, Acts of Settlement and Uniformity of 1559 as a compromise. In fact, Elizabeth believed that faith was personal and did not wish, as Francis Bacon put it, to "make windows into men's hearts and secret thoughts".

Though Elizabeth followed a largely defensive foreign policy, her reign raised England's status abroad. "She is only a woman, only mistress of half an island," marvelled Pope Sixtus V, "and yet she makes herself feared by Spain, by France, by Holy Roman Empire, the Empire, by all".Somerset, 727. Under Elizabeth, the nation gained a new self-confidence and sense of sovereignty, as Christendom fragmented. Elizabeth was the first Tudor to recognise that a monarch ruled by popular consent. She therefore always worked with parliament and advisers she could trust to tell her the truth—a style of government that her Stuart successors failed to follow. Some historians have called her lucky; she believed that God was protecting her. Priding herself on being "mere English", Elizabeth trusted in God, honest advice, and the love of her subjects for the success of her rule.Starkey ''Elizabeth: Woman'', 6–7. In a prayer, she offered thanks to God that:

''Annales Rerum Gestarum Angliae et Hiberniae Regnante Elizabetha.''

(1615 and 1625.) Hypertext edition, with English translation. Dana F. Sutton (ed.), 2000. Retrieved 7 December 2007. * Clapham, John. ''Elizabeth of England''. E. P. Read and Conyers Read (eds). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951. .

Elizabeth I

at the official website of the British monarchy

Elizabeth I

at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Elizabeth 01 Of England Elizabeth I, People of the Elizabethan era, 1533 births 1603 deaths 16th-century English monarchs 16th-century English women 16th-century English writers 16th-century Irish monarchs 16th-century English translators 17th-century English monarchs 17th-century English people 17th-century English women 17th-century Irish monarchs 17th-century queens regnant Burials at Westminster Abbey Children of Henry VIII English Anglicans English people of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) English people of Welsh descent English pretenders to the French throne English women poets Founders of English schools and colleges House of Tudor People excommunicated by the Catholic Church People from Greenwich People of the French Wars of Religion Prisoners in the Tower of London Protestant monarchs Queens regnant of England Regicides of Mary, Queen of Scots Reputed virgins 16th-century queens regnant

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last monarch of the House of Tudor

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

.

Elizabeth was the only surviving child of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

and his second wife, Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

. When Elizabeth was two years old, her parents' marriage was annulled, her mother was executed, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

. Henry restored her to the line of succession when she was 10, via the Third Succession Act 1543. After Henry's death in 1547, Elizabeth's younger half-brother Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour and the first E ...

ruled until his own death in 1553, bequeathing the crown to a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

cousin, Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

, and ignoring the claims of his two half-sisters, the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

and the younger Elizabeth, in spite of statutes to the contrary. Edward's will was set aside within weeks of his death and Mary became queen, deposing and executing Jane. During Mary's reign, Elizabeth was imprisoned for nearly a year on suspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Upon her half-sister's death in 1558, Elizabeth succeeded to the throne and set out to rule by good counsel. She depended heavily on a group of trusted advisers led by William Cecil, whom she created Baron Burghley

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knig ...

. One of her first actions as queen was the establishment of an English Protestant church, of which she became the supreme governor

The supreme governor of the Church of England is the titular head of the Church of England, a position which is vested in the British monarch. Queen and Church > Queen and Church of England">The Monarchy Today > Queen and State > Queen and Churc ...

. This era, later named the Elizabethan Religious Settlement

The Elizabethan Religious Settlement is the name given to the religious and political arrangements made for England during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Implemented between 1559 and 1563, the settlement is considered the end of the E ...

, would evolve into the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. It was expected that Elizabeth would marry and produce an heir; however, despite numerous courtships, she never did, and because of this she is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen". She was eventually succeeded by her first cousin twice removed, James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

.

In government, Elizabeth was more moderate than her father and siblings had been.Starkey ''Elizabeth: Woman'', 5. One of her mottoes

A motto (derived from the Latin language, Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian language, Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a Sentence (linguistics), sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of a ...

was ("I see and keep silent"). In religion, she was relatively tolerant and avoided systematic persecution. After the pope declared her illegitimate in 1570, which in theory released English Catholics from allegiance to her, several conspiracies threatened her life, all of which were defeated with the help of her ministers' secret service, run by Sir Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her "spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wals ...

. Elizabeth was cautious in foreign affairs, manoeuvring between the major powers of France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. She half-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourced military campaigns in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, France, and Ireland. By the mid-1580s, England could no longer avoid war with Spain

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

.

As she grew older, Elizabeth became celebrated for her virginity

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

. A cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

grew around her which was celebrated in the portraits, pageants, and literature of the day. Elizabeth's reign became known as the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

. The period is famous for the flourishing of English drama

Drama was introduced to Britain from Europe by the Romans, and auditoriums were constructed across the country for this purpose.

But England didn't exist until hundreds of years after the Romans left.

Medieval period

By the medieval period, t ...

, led by playwrights such as William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the ...

, the prowess of English maritime adventurers, such as Francis Drake

Sir Francis Drake ( – 28 January 1596) was an English explorer, sea captain, privateer, slave trader, naval officer, and politician. Drake is best known for his circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition, from 1577 to 1580 (t ...

and Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

, and for the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

. Some historians depict Elizabeth as a short-tempered, sometimes indecisive ruler, who enjoyed more than her fair share of luck. Towards the end of her reign, a series of economic and military problems weakened her popularity. Elizabeth is acknowledged as a charismatic performer ("Gloriana") and a dogged survivor ("Good Queen Bess") in an era when government was ramshackle and limited, and when monarchs in neighbouring countries faced internal problems that jeopardised their thrones. After the short, disastrous reigns of her half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne provided welcome stability for the kingdom and helped to forge a sense of national identity.

Early life

Elizabeth was born at

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

on 7 September 1533 and was named after her grandmothers, Elizabeth of York

Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503) was Queen of England from her marriage to King Henry VII on 18 January 1486 until her death in 1503. Elizabeth married Henry after his victory at the Battle of Bosworth Field, which ma ...

and Lady Elizabeth Howard

Elizabeth Boleyn, Countess of Wiltshire (born Lady Elizabeth Howard; c. 1480 – 3 April 1538) was an English noblewoman, noted for being the mother of Anne Boleyn and as such the maternal grandmother of Elizabeth I of England. The eldest daugh ...

. She was the second child of Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

born in wedlock to survive infancy. Her mother was Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key ...

. At birth, Elizabeth was the heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of an heir apparent or a new heir presumptive with a better claim to the position in question.

...

to the English throne. Her elder half-sister Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

had lost her position as a legitimate heir when Henry annulled his marriage to Mary's mother, Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, to marry Anne, with the intent to sire a male heir and ensure the Tudor succession. She was baptised on 10 September 1533, and her godparents were Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build the case for the annulment of Henry' ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

; Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter; Elizabeth Stafford, Duchess of Norfolk

Lady Elizabeth Stafford (''later'' Duchess of Norfolk) (c.1497 – 30 November 1558) was an English aristocrat. She was the eldest daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Lady Eleanor Percy. By marriage she became Duchess of Norf ...

; and Margaret Wotton, Dowager Marchioness of Dorset. A canopy was carried at the ceremony over the infant by her uncle George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford

George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford (c. 1504 – 17 May 1536) was an English courtier and nobleman who played a prominent role in the politics of the early 1530s. He was the brother of Anne Boleyn, from 1533 the second wife of King He ...

; John Hussey, Baron Hussey of Sleaford; Lord Thomas Howard

Lord Thomas Howard (1511 – 31 October 1537) was an English courtier at the court of King Henry VIII. He is chiefly known for his marriage (later invalidated by Henry) to Lady Margaret Douglas (1515–1578), the daughter of Henry VIII's si ...

; and William Howard, Baron Howard of Effingham.

Elizabeth was two years and eight months old when her mother was beheaded on 19 May 1536, four months after Catherine of Aragon's death from natural causes. Elizabeth was declared illegitimate and deprived of her place in the royal succession. Eleven days after Anne Boleyn's execution, Henry married Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (c. 150824 October 1537) was List of English consorts, Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their Wives of Henry VIII, marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen followi ...

. Queen Jane died the next year shortly after the birth of their son, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

, who was the undisputed heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the throne. Elizabeth was placed in her half-brother's household and carried the chrisom

Anciently, a chrisom, or "chrisom-cloth," was the face-cloth, or piece of linen laid over a child's head when they were baptised or christened. Originally, the purpose of the chrisom-cloth was to keep the ''chrism'', a consecrated oil, from accid ...

, or baptismal cloth, at his christening.

Elizabeth's first

Elizabeth's first governess

A governess is a largely obsolete term for a woman employed as a private tutor, who teaches and trains a child or children in their home. A governess often lives in the same residence as the children she is teaching. In contrast to a nanny, th ...

, Margaret Bryan

Margaret Bryan, Baroness Bryan (c. 1468 – c. 1551/52) was lady governess to the children of King Henry VIII of England, the future monarchs Mary I, Elizabeth I, and Edward VI, as well as the illegitimate Henry FitzRoy.She was also Lady Govern ...

, wrote that she was "as toward a child and as gentle of conditions as ever I knew any in my life". Catherine Champernowne, better known by her later, married name of Catherine "Kat" Ashley, was appointed as Elizabeth's governess in 1537, and she remained Elizabeth's friend until her death in 1565. Champernowne taught Elizabeth four languages: French, Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

, Italian, and Spanish. By the time William Grindal

William Grindal (died 1548) was an English scholar. A dear friend, pupil and protégé of Roger Ascham's at St John's College, Cambridge, he became tutor to Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen Elizabeth, and laid the foundations of her education ...

became her tutor in 1544, Elizabeth could write English, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and Italian. Under Grindal, a talented and skilful tutor, she also progressed in French and Greek.Loades, 8–10. By the age of 12, she was able to translate her stepmother Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr (sometimes alternatively spelled Katherine, Katheryn, Kateryn, or Katharine; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen of England and Ireland as the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 12 July 1543 until ...

's religious work ''Prayers or Meditations

''Prayers or Meditations'', written in 1545 by the English queen Catherine Parr, was the first book published in England by a woman under her own name and in the English language. It first appeared in print on 8 June 1545. Preceded in the previou ...

'' from English into Italian, Latin, and French, which she presented to her father as a New Year's gift. From her teenage years and throughout her life, she translated works in Latin and Greek by numerous classical authors, including the ''Pro Marcello

''Pro Marcello'' is a speech by Marcus Tullius Cicero. It is Latin for ''On behalf of Marcellus''.

Background

Marcus Claudius Marcellus was descended from an illustrious Roman family, and had been Consul with Servius Sulpicius Rufus, in which offi ...

'' of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, the ''De consolatione philosophiae

''On the Consolation of Philosophy'' ('' la, De consolatione philosophiae'')'','' often titled as ''The Consolation of Philosophy'' or simply the ''Consolation,'' is a philosophical work by the Roman statesman Boethius. Written in 523 while he ...

'' of Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

, a treatise by Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

, and the ''Annals

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

'' of Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

. A translation of Tacitus from Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace is the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. It is situated in north Lambeth, London, on the south bank of the River Thames, south-east of the Palace of Westminster, which houses Parliament, on the opposite ...

Library, one of only four surviving English translations from the early modern era, was confirmed as Elizabeth's own in 2019, after a detailed analysis of the handwriting and paper was undertaken.

After Grindal died in 1548, Elizabeth received her education under her brother Edward's tutor, Roger Ascham

Roger Ascham (; c. 151530 December 1568)"Ascham, Roger" in ''The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 617. was an English scholar and didactic writer, famous for his prose style, ...

, a sympathetic teacher who believed that learning should be engaging. Current knowledge of Elizabeth's schooling and precocity comes largely from Ascham's memoirs. By the time her formal education ended in 1550, Elizabeth was one of the best educated women of her generation. At the end of her life, she was believed to speak the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

, Cornish, Scottish, and Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

s in addition to those mentioned above. The Venetian ambassador stated in 1603 that she "possessed heselanguages so thoroughly that each appeared to be her native tongue". Historian Mark Stoyle

Mark J. Stoyle is a Tudor and Stuart British historian who specializes in the English Civil War, the nature of magic and witchcraft and the identity of key areas such as Cornwall and Wales during the early modern period. He is Professor at the ...

suggests that she was probably taught Cornish by William Killigrew, Groom of the Privy Chamber and later Chamberlain of the Exchequer.

Thomas Seymour

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector

Henry VIII died in 1547 and Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI, became king at the age of nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soon married Thomas Seymour, Baron Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and the brother of Lord Protector Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset (150022 January 1552) (also 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp), also known as Edward Semel, was the eldest surviving brother of Queen Jane Seymour (d. 1537), the third wife of King Henry V ...

. The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

. There Elizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historians believe affected her for the rest of her life.Loades, 11. Thomas Seymour engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-old Elizabeth, including entering her bedroom in his nightgown, tickling her, and slapping her on the buttocks. Elizabeth rose early and surrounded herself with maids to avoid his unwelcome morning visits. Parr, rather than confront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in. Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held her while he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces". However, after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this state of affairs. In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

Thomas Seymour nevertheless continued scheming to control the royal family and tried to have himself appointed the governor of the King's person. When Parr died after childbirth on 5 September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intent on marrying her. Her governess Kat Ashley

Katherine Astley (née Champernowne; circa 1502 – 18 July 1565), also known as Kat Astley, was the first close friend, governess, and Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Sh ...

, who was fond of Seymour, sought to convince Elizabeth to take him as her husband. She tried to convince Elizabeth to write to Seymour and "comfort him in his sorrow", but Elizabeth claimed that Thomas was not so saddened by her stepmother's death as to need comfort.

In January 1549, Seymour was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of conspiring to depose his brother Somerset as Protector, marry Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey ( 1537 – 12 February 1554), later known as Lady Jane Dudley (after her marriage) and as the "Nine Days' Queen", was an English noblewoman who claimed the throne of England and Ireland from 10 July until 19 July 1553.

Jane was ...

to King Edward VI, and take Elizabeth as his own wife. Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house, a leading example of the prodigy house, was built in 1611 by Robert Ceci ...

, would admit nothing. Her stubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Robert Tyrwhitt

Robert Tyrwhitt (1735–1817) was an English academic, known as a Unitarian.

Life

Born in London, he was younger son of Robert Tyrwhitt (1698–1742), residentiary canon of St Paul's Cathedral, by his wife Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Edmund G ...

, who reported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty".Neale, 33. Seymour was beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Reign of Mary I

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, aged 15. His will ignored the Succession to the Crown Act 1543, excluded both Mary and Elizabeth from the succession, and instead declared as his heir Lady Jane Grey, granddaughter of Henry VIII's younger sisterMary Tudor, Queen of France

Mary Tudor (; 18 March 1496 – 25 June 1533) was an English princess who was briefly Queen of France as the third wife of King Louis XII. Louis was more than 30 years her senior. Mary was the fifth child of Henry VII of England and Elizabeth of ...

. Jane was proclaimed queen by the privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

, but her support quickly crumbled, and she was deposed after nine days. On 3 August 1553, Mary rode triumphantly into London, with Elizabeth at her side.

The show of solidarity between the sisters did not last long. Mary, a devout Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, was determined to crush the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

faith in which Elizabeth had been educated, and she ordered that everyone attend Catholic Mass; Elizabeth had to outwardly conform. Mary's initial popularity ebbed away in 1554 when she announced plans to marry Philip of Spain, the son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, french: Charles Quint, it, Carlo V, nl, Karel V, ca, Carles V, la, Carolus V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain ( Castile and Aragon) fro ...

and an active Catholic. Discontent spread rapidly through the country, and many looked to Elizabeth as a focus for their opposition to Mary's religious policies.

In January and February 1554, Wyatt's rebellion broke out; it was soon suppressed. Elizabeth was brought to court and interrogated regarding her role, and on 18 March, she was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. Elizabeth fervently protested her innocence. Though it is unlikely that she had plotted with the rebels, some of them were known to have approached her. Mary's closest confidant, Emperor Charles's ambassador Simon Renard

Simon Renard, Sieur of Bermont and Lieutenant of Aumont or Amont, (1513- 8 August 1573) was a Burgundian diplomat who served as an advisor to Emperor Charles V and his son Philip II of Spain, who were also counts of Burgundy. Renard had the ...

, argued that her throne would never be safe while Elizabeth lived; and Lord Chancellor Stephen Gardiner

Stephen Gardiner (27 July 1483 – 12 November 1555) was an English Catholic bishop and politician during the English Reformation period who served as Lord Chancellor during the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip.

Early life

Gardiner was b ...

, worked to have Elizabeth put on trial. Elizabeth's supporters in the government, including William Paget, Baron Paget, convinced Mary to spare her sister in the absence of hard evidence against her. Instead, on 22 May, Elizabeth was moved from the Tower to Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock, New York, Woodstock. ...

, where she was to spend almost a year under house arrest in the charge of Henry Bedingfeld

Sir Henry Bedingfeld (1505–1583F. Blomefield, 'Oxburgh', in ''An Essay Towards A Topographical History of the County of Norfolk'', Vol. 6: Hundred of South Greenhoe (W. Miller, London 1807)pp. 168-97(British History Online), accessed 5 Febru ...

. Crowds cheered her all along the way.Loades, 29.

On 17 April 1555, Elizabeth was recalled to court to attend the final stages of Mary's apparent pregnancy. If Mary and her child died, Elizabeth would become queen, but if Mary gave birth to a healthy child, Elizabeth's chances of becoming queen would recede sharply. When it became clear that Mary was not pregnant, no one believed any longer that she could have a child. Elizabeth's succession seemed assured.

King Philip, who ascended the Spanish throne in 1556, acknowledged the new political reality and cultivated his sister-in-law. She was a better ally than the chief alternative, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

, who had grown up in France and was betrothed to the Dauphin of France

Dauphin of France (, also ; french: Dauphin de France ), originally Dauphin of Viennois (''Dauphin de Viennois''), was the title given to the heir apparent to the throne of France from 1350 to 1791, and from 1824 to 1830. The word ''dauphin'' ...

. When his wife fell ill in 1558, Philip sent the Count of Feria to consult with Elizabeth. This interview was conducted at Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house, a leading example of the prodigy house, was built in 1611 by Robert Ceci ...

, where she had returned to live in October 1555. By October 1558, Elizabeth was already making plans for her government. Mary recognised Elizabeth as her heir on 6 November 1558, and Elizabeth became queen when Mary died on 17 November.

Accession

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared her intentions to her council and other peers who had come to Hatfield to swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of her adoption of the medieval political theology

Political theology is a term which has been used in discussion of the ways in which theological concepts or ways of thinking relate to politics. The term ''political theology'' is often used to denote religious thought about political principled qu ...

of the sovereign's "two bodies": the body natural and the body politic

The body politic is a polity—such as a city, realm, or state—considered metaphorically as a physical body. Historically, the sovereign is typically portrayed as the body's head, and the analogy may also be extended to other anatomical par ...

:

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of the coronation ceremony

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by the citizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strong Protestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responses endeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfully ravished". The following day, 15 January 1559, a date chosen by her astrologer John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divinatio ...

, Elizabeth was crowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe

Owen Oglethorpe ( – 31 December 1559) was an English academic and Roman Catholic Bishop of Carlisle, 1557–1559.

Childhood and Education

Oglethorpe was born in Tadcaster, Yorkshire, England (where he later founded a school), the third son ...

, the Catholic bishop of Carlisle

The Bishop of Carlisle is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Carlisle in the Province of York.

The diocese covers the county of Cumbria except for Alston Moor and the former Sedbergh Rural District. The see is in the city of Car ...

, in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. She was then presented for the people's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes, trumpets, drums, and bells. Although Elizabeth was welcomed as queen in England, the country was still in a state of anxiety over the perceived Catholic threat at home and overseas, as well as the choice of whom she would marry.

Church settlement

Elizabeth's personal religious convictions have been much debated by scholars. She was a Protestant, but kept Catholic symbols (such as thecrucifix

A crucifix (from Latin ''cruci fixus'' meaning "(one) fixed to a cross") is a cross with an image of Jesus on it, as distinct from a bare cross. The representation of Jesus himself on the cross is referred to in English as the ''corpus'' (Lati ...

), and downplayed the role of sermons in defiance of a key Protestant belief.

Elizabeth and her advisers perceived the threat of a Catholic crusade against heretical England. The queen therefore sought a Protestant solution that would not offend Catholics too greatly while addressing the desires of English Protestants, but she would not tolerate the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

s, who were pushing for far-reaching reforms. As a result, the Parliament of 1559 started to legislate for a church based on the Protestant settlement of Edward VI, with the monarch as its head, but with many Catholic elements, such as vestments

Vestments are liturgical garments and articles associated primarily with the Christian religion, especially by Eastern Churches, Catholics (of all rites), Anglicans, and Lutherans. Many other groups also make use of liturgical garments; this w ...

.

The House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

backed the proposals strongly, but the bill of supremacy met opposition in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, particularly from the bishops. Elizabeth was fortunate that many bishoprics were vacant at the time, including the Archbishopric of Canterbury

The Province of Canterbury, or less formally the Southern Province, is one of two ecclesiastical provinces which constitute the Church of England. The other is the Province of York (which consists of 12 dioceses).

Overview

The Province consist ...

. This enabled supporters amongst peers to outvote the bishops and conservative peers. Nevertheless, Elizabeth was forced to accept the title of Supreme Governor of the Church of England

The supreme governor of the Church of England is the titular head of the Church of England, a position which is vested in the British monarch. Queen and Church > Queen and Church of England">The Monarchy Today > Queen and State > Queen and Chur ...

rather than the more contentious title of Supreme Head

The title of Supreme Head of the Church of England was created in 1531 for King Henry VIII when he first began to separate the Church of England from the authority of the Holy See and allegiance to the papacy, then represented by Pope Clement VI ...

, which many thought unacceptable for a woman to bear. The new Act of Supremacy

The Acts of Supremacy are two acts passed by the Parliament of England in the 16th century that established the English monarchs as the head of the Church of England; two similar laws were passed by the Parliament of Ireland establishing the Eng ...

became law on 8 May 1559. All public officials were forced to swear an oath of loyalty to the monarch as the supreme governor or risk disqualification from office; the heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

laws were repealed, to avoid a repeat of the persecution of dissenters by Mary. At the same time, a new Act of Uniformity was passed, which made attendance at church and the use of the 1559 ''Book of Common Prayer'' (an adapted version of the 1552 prayer book) compulsory, though the penalties for recusancy

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

, or failure to attend and conform, were not extreme.

Marriage question

From the start of Elizabeth's reign it was expected that she would marry, and the question arose to whom. Although she received many offers, she never married and remained childless; the reasons for this are not clear. Historians have speculated that Thomas Seymour had put her off sexual relationships. She considered several suitors until she was about fifty. Her last courtship was withFrancis, Duke of Anjou

'' Monsieur'' Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (french: Hercule François; 18 March 1555 – 10 June 1584) was the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early years

He was scarred by smallpox at age eight, a ...

, 22 years her junior. While risking possible loss of power like her sister, who played into the hands of King Philip II of Spain, marriage offered the chance of an heir. However, the choice of a husband might also provoke political instability or even insurrection.

Robert Dudley

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife

In the spring of 1559, it became evident that Elizabeth was in love with her childhood friend Robert Dudley. It was said that his wife Amy

Amy is a female given name, sometimes short for Amanda, Amelia, Amélie, or Amita. In French, the name is spelled ''"Aimée"''.

People A–E

* Amy Acker (born 1976), American actress

* Amy Vera Ackman, also known as Mother Giovanni (1886– ...

was suffering from a "malady in one of her breasts" and that the queen would like to marry Robert if his wife should die. By the autumn of 1559, several foreign suitors were vying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in ever more scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with her favourite

A favourite (British English) or favorite (American English) was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In post-classical and early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated si ...

was not welcome in England: "There is not a man who does not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marry none but the favoured Robert." Amy Dudley died in September 1560, from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner's inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a coro ...

finding of accident, many people suspected her husband of having arranged her death so that he could marry the queen. Elizabeth seriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However, William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton

Sir Nicholas Throckmorton (or Throgmorton) (c. 1515/151612 February 1571) was an English diplomat and politician, who was an ambassador to France and later Scotland, and played a key role in the relationship between Elizabeth I of Englan ...

, and some conservative peers

Peers may refer to:

People

* Donald Peers

* Edgar Allison Peers, English academician

* Gavin Peers

* John Peers, Australian tennis player

* Kerry Peers

* Mark Peers

* Michael Peers

* Steve Peers

* Teddy Peers (1886–1935), Welsh international ...

made their disapproval unmistakably clear. There were even rumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage took place.

Among other marriage candidates being considered for the queen, Robert Dudley continued to be regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade. Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she no longer meant to marry him herself. She raised Dudley to the peerage as Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

Early creations ...

in 1564. In 1578, he finally married Lettice Knollys

Lettice Knollys ( , sometimes latinized as Laetitia, alias Lettice Devereux or Lettice Dudley), Countess of Essex and Countess of Leicester (8 November 1543Adams 2008a – 25 December 1634), was an English noblewoman and mother to the courtier ...

, to whom the queen reacted with repeated scenes of displeasure and lifelong hatred. Still, Dudley always "remained at the centre of lizabeth'semotional life", as historian Susan Doran has described the situation. He died shortly after the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

in 1588. After Elizabeth's own death, a note from him was found among her most personal belongings, marked "his last letter" in her handwriting.

Foreign candidates

Marriage negotiations constituted a key element in Elizabeth's foreign policy.Haigh, 17. She turned down the hand of Philip, her half-sister's widower, early in 1559 but for several years entertained the proposal of KingEric XIV of Sweden

Eric XIV ( sv, Erik XIV; 13 December 153326 February 1577) was King of Sweden from 1560 until he was deposed in 1569. Eric XIV was the eldest son of Gustav I (1496–1560) and Catherine of Saxe-Lauenburg (1513–1535). He was also ruler of Es ...

. Earlier in Elizabeth's life a Danish match for her had been discussed; Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

had proposed one with the Danish prince Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp

Adolf of Denmark or Adolf of Holstein-Gottorp (25 January 1526 –1 October 1586) was the first Duke of Holstein-Gottorp from the line of Holstein-Gottorp of the House of Oldenburg.

He was the third son of King Frederick I of Denmark and hi ...

, in 1545, and Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, suggested a marriage with Prince Frederick (later Frederick II) several years later, but the negotiations had abated in 1551. In the years around 1559 a Dano-English Protestant alliance was considered, and to counter Sweden's proposal, King Frederick II proposed to Elizabeth in late 1559.

For several years she also seriously negotiated to marry Philip's cousin

For several years she also seriously negotiated to marry Philip's cousin Charles II, Archduke of Austria

Charles II Francis of Austria (german: Karl II. Franz von Innerösterreich) (3 June 1540 – 10 July 1590) was an Archduke of Austria and ruler of Inner Austria (Styria, Carniola, Carinthia and Gorizia) from 1564. He was a member of the House o ...

. By 1569, relations with the Habsburgs had deteriorated. Elizabeth considered marriage to two French Valois princes in turn, first Henry, Duke of Anjou

Henry III (french: Henri III, né Alexandre Édouard; pl, Henryk Walezy; lt, Henrikas Valua; 19 September 1551 – 2 August 1589) was King of France from 1574 until his assassination in 1589, as well as King of Poland and Grand Duke of Li ...

, and then from 1572 to 1581 his brother Francis, Duke of Anjou, formerly Duke of Alençon. This last proposal was tied to a planned alliance against Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands, also called the Catholic Netherlands, were the parts of the Low Countries belonging to the Holy Roman Empire which were at first largely controlled by Habsburg Spain (Spanish Netherlands, 1556–1714) and later by the A ...

. Elizabeth seems to have taken the courtship seriously for a time, and wore a frog-shaped earring that Francis had sent her.

In 1563, Elizabeth told an imperial envoy: "If I follow the inclination of my nature, it is this: beggar-woman and single, far rather than queen and married". Later in the year, following Elizabeth's illness with smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, the succession question became a heated issue in Parliament. Members urged the queen to marry or nominate an heir, to prevent a civil war upon her death. She refused to do either. In April she prorogued

A legislative session is the period of time in which a legislature, in both parliamentary and presidential systems, is convened for purpose of lawmaking, usually being one of two or more smaller divisions of the entire time between two elections ...

the Parliament, which did not reconvene until she needed its support to raise taxes in 1566.

Having previously promised to marry, she told an unruly House:

By 1570, senior figures in the government privately accepted that Elizabeth would never marry or name a successor. William Cecil was already seeking solutions to the succession problem. For her failure to marry, Elizabeth was often accused of irresponsibility. Her silence, however, strengthened her own political security: she knew that if she named an heir, her throne would be vulnerable to a coup; she remembered the way that "a second person, as I have been" had been used as the focus of plots against her predecessor.

Virginity

Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity related to that of the Virgin Mary. In poetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin, a goddess, or both, not as a normal woman. At first, only Elizabeth made a virtue of her ostensible virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, in the end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shall declare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin".Haigh, 23. Later on, poets and writers took up the theme and developed aniconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

that exalted Elizabeth. Public tributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion of opposition to the queen's marriage negotiations with the Duke of Alençon. Ultimately, Elizabeth would insist she was married to her kingdom and subjects, under divine protection. In 1599, she spoke of "all my husbands, my good people".

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body.

This claim of virginity was not universally accepted. Catholics accused Elizabeth of engaging in "filthy lust" that symbolically defiled the nation along with her body. Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

said that one of the great questions of Europe was "whether Queen Elizabeth was a maid or no".

A central issue, when it comes to the question of Elizabeth's virginity, was whether the queen ever consummated her love affair with Robert Dudley. In 1559, she had Dudley's bedchambers moved next to her own apartments. In 1561, she was mysteriously bedridden with an illness that caused her body to swell.

In 1587, a young man calling himself Arthur Dudley

Arthur Dudley was a 16th-century man famous for the controversial claim that he was the son of Queen Elizabeth I and Robert Dudley, a man known to have had a (not necessarily consummated) long love affair with the queen.

Queen Elizabeth I and R ...

was arrested on the coast of Spain under suspicion of being a spy. The man claimed to be the illegitimate son of Elizabeth and Robert Dudley, with his age being consistent with birth during the 1561 illness. He was taken to Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

for investigation, where he was examined by Francis Englefield

Sir Francis Englefield (c. 1522 – 1596) was an English courtier and Roman Catholic exile.

Family

Francis Englefield, born about 1522, was the eldest son of Thomas Englefield (1488–1537) of Englefield, Berkshire, Justice of the Common P ...